Amebiasis Prevention Quiz

1. How is amebiasis primarily transmitted?

2. What is the recommended duration for effective hand-washing?

3. Which of these is NOT a key transmission vector in schools?

4. What is the primary way to eliminate cysts in drinking water?

5. Which action helps reduce amebiasis outbreaks in schools?

Quick Takeaways

- Amebiasis spreads mainly through contaminated water and food, making school environments high‑risk.

- Teaching amebiasis prevention saves lives, reduces absenteeism, and cuts healthcare costs.

- Effective lessons combine hand‑washing drills, safe‑water policies, and food‑handling basics.

- Partnering with local health agencies creates sustainable school health programs.

- Simple checklists help teachers monitor hygiene practices daily.

When a handful of kids in a classroom catch a stomach parasite, the ripple effect hits teachers, parents, and the local health system. Amebiasis is an intestinal infection caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. The parasite lives in contaminated water or food and spreads via the fecal‑oral route. In places where school sanitation is weak, an outbreak can spread faster than a gossip chain.

Why Amebiasis Still Threatens Schools

Even in high‑income nations like the UK, pockets of deprivation create conditions where amebiasis can slip through the cracks. A 2022 World Health Organization report noted that 1.7million new cases occur each year in Europe, with a noticeable concentration in densely populated urban schools that lack proper hand‑washing facilities.

Teachers often see the fallout as increased sick days, low concentration, and occasional hospital visits. The CDC estimates that each case of amebiasis costs the NHS roughly £2,300 in treatment and lost productivity. Multiply that by dozens of cases and the numbers become alarming.

How Amebiasis Spreads: The Science Behind Transmission

Understanding the parasite’s life cycle is the first step to stopping it. Entamoeba histolytica produces cysts that survive for weeks in moist environments. When a child touches a contaminated surface - a faucet handle, a shared snack, or a dusty notebook - and then puts their hand in their mouth, the cysts hatch and invade the colon.

Key transmission vectors in schools include:

- Inadequate hand‑washing stations near cafeterias.

- Shared water fountains that are rarely cleaned.

- Food prepared in bulk without proper hygiene checks.

Each vector represents a teachable moment.

Core Prevention Lessons for the Classroom

Embedding prevention into the curriculum doesn’t require a full‑blown biology degree. Below is a modular lesson plan that can fit into a 30‑minute health class or a cross‑subject activity.

- Lesson 1: The Hidden Enemy - Use a simple diagram of the cyst life cycle. Ask students to label where the parasite lives outside the body.

- Lesson 2: Hand‑Hygiene Hero - Demonstrate the 20‑second soap‑and‑water technique. Let kids practice with a glitter test: rub glitter on one hand, wash, and see how much remains.

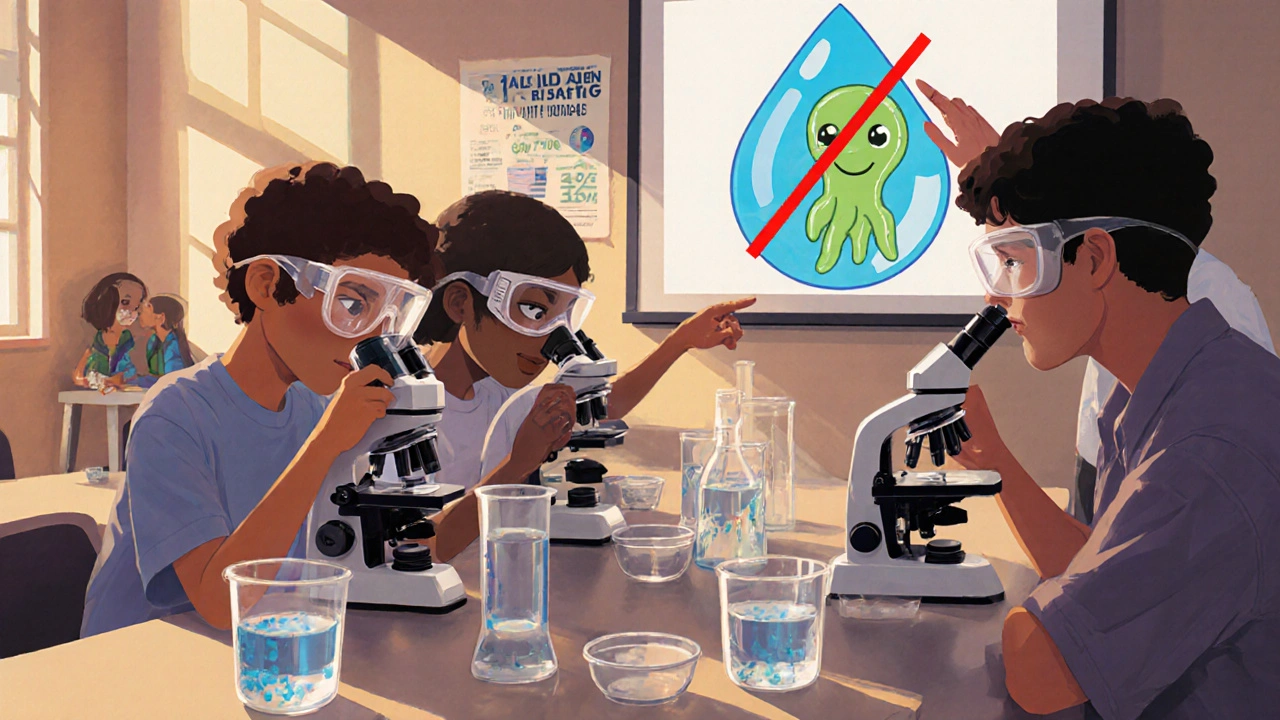

- Lesson 3: Safe Water - Explain how boiling or using certified filters removes cysts. Include a quick experiment: compare filtered versus unfiltered water under a microscope (or a trusted video).

- Lesson 4: Food‑Safety Facts - Discuss why raw vegetables need thorough washing and why leftovers must be reheated.

- Lesson 5: Community Action - Have students create posters for the school hallway promoting the three R’s: Read (labels), Rinse (hands), Refresh (water).

Building a School‑Wide Health Program

One lesson sparks awareness, but a program cements habits. Below is a step‑by‑step blueprint for administrators.

- Assess Infrastructure: Survey every hand‑washing station, water fountain, and kitchen area. Record availability of soap, paper towels, and regular cleaning schedules.

- Partner with Local Health Agencies: Invite officials from the Birmingham Public Health Department or the World Health Organization to provide training materials.

- Develop Policy: Draft a school health policy that mandates hand‑washing before meals, after bathroom use, and after outdoor play.

- Supply Essentials: Allocate budget for soap dispensers, hand‑dryers, and portable water filters. A low‑cost option is a chlorine tablet kit that treats up to 1,000L of water per month.

- Train Staff: Conduct a brief workshop for teachers, cafeteria workers, and cleaning crews on spotting early symptoms and reinforcing hygiene.

- Monitor & Evaluate: Use a simple logbook where teachers tick off hand‑washing compliance. Review monthly and adjust as needed.

Real‑World Success Stories

In 2023, a secondary school in West Midlands partnered with the local health board to launch an “Amebiasis‑Free Campus” initiative. Within six months, reported cases fell from eight to zero. The key drivers were:

- Installation of sensor‑activated faucets that dispense the right amount of soap.

- Monthly “Clean Water” drills where students test water samples with rapid test strips.

- Student‑led peer education clubs that created viral TikTok videos on proper hand‑washing.

Another case from a primary school in Dublin showed a 30% reduction in absenteeism after integrating a three‑day hygiene week into the curriculum.

Quick Checklist for Teachers

| Task | When | Who Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Soap dispenser filled | Start of each period | Classroom monitor |

| Hand‑washing demo | Before lunch | Teacher |

| Water filter serviced | Weekly | Facilities staff |

| Food safety poster visible | Daily | Student council |

Frequently Asked Questions

How is amebiasis diagnosed in children?

Doctors look for cysts or trophozoites in stool samples using microscopy or a rapid antigen test. A positive result usually triggers a short course of metronidazole followed by a luminal agent.

Can a single hand‑washing session prevent infection?

Yes, if the session lasts at least 20seconds, uses soap, and covers all hand surfaces. The friction helps remove cysts that cling to skin.

What inexpensive water‑treatment method works for schools?

Chlorine tablets are cheap (≈£0.05 per tablet) and can disinfect up to 1,000L of water. They inactivate cysts within 30minutes.

How often should schools review their hygiene policies?

A formal review every six months ensures policies stay aligned with any new guidance from health authorities and allows for budget adjustments.

Are there vaccines for amebiasis?

Not yet. Research is ongoing, but for now education and sanitation remain the most effective defenses.