When a drug warning pops up-whether it’s on your screen at work, in a patient’s chart, or on the news-it’s easy to assume it applies to everything in that category. But that’s not always true. Some safety alerts hit an entire class of drugs. Others target just one. Mixing them up can lead to unnecessary changes in treatment-or worse, missed risks. Knowing the difference between a class-wide and a drug-specific safety alert isn’t just for regulators. It matters to every clinician, pharmacist, and patient who relies on accurate information to make safe choices.

What’s the Difference Between Class-Wide and Drug-Specific Alerts?

A class-wide safety alert means the risk applies to every drug in a therapeutic group because of how the whole class works. For example, all ACE inhibitors carry a risk of angioedema. That’s not because one brand is faulty-it’s because they all block the same enzyme in the body. If one drug in the class causes swelling of the face or throat, the mechanism is shared across the group. A drug-specific alert, on the other hand, targets just one medication. It’s usually because of a unique chemical quirk. Take cerivastatin: it was pulled from the market in 2001 because of deadly muscle damage (rhabdomyolysis). But other statins like atorvastatin and rosuvastatin stayed on shelves. Why? Their metabolism and structure were different enough to avoid the same extreme risk. The FDA started making this distinction official in the 1980s with black box warnings-the strongest type of safety alert. Back then, tetracycline got one for photosensitivity. Today, there are over 22 million adverse event reports in the FDA’s FAERS database. But not every signal means the whole class is dangerous. The real challenge is telling the difference before patients are harmed.How Regulators Decide: Evidence Thresholds

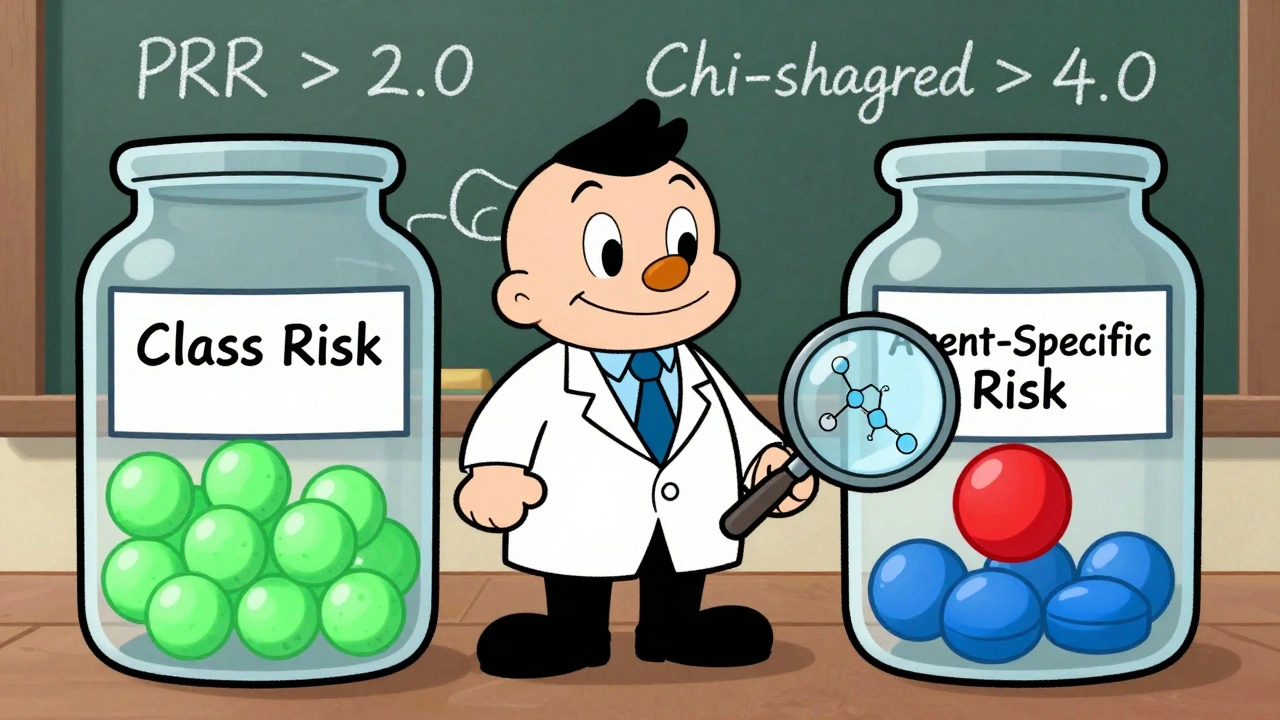

The FDA doesn’t guess. They use hard data. To label a warning as class-wide, they need consistent signals across multiple drugs in the same group. One report? Not enough. Three or more drugs showing the same rare side effect? That’s a red flag. They look at three things:- Quantitative signals: Metrics like the Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR) above 2.0 and Chi-squared values over 4.0 across multiple databases. These numbers show whether the side effect is happening more often than random chance.

- Pharmacological similarity: Drugs in the same class share the same target, metabolism, or chemical structure. If they all work the same way, a side effect in one suggests it could happen in others.

- Real-world evidence: Post-market studies, like ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), confirmed that all 12 testosterone products raised blood pressure-not just two or three. That’s how the 2023 class-wide warning for cardiovascular risk came about.

Why It Matters: Real-World Consequences

Getting this wrong has real consequences. When the FDA issued a class-wide warning for fluoroquinolone antibiotics in 2018-citing risks of disabling tendon, nerve, and muscle damage-prescribing dropped by 17%. That’s good for safety. But it also meant some patients with complicated urinary tract infections lost a critical tool. Doctors had to turn to less effective or more expensive alternatives. Compare that to valdecoxib (Bextra), withdrawn in 2004 due to severe skin reactions. Celecoxib (Celebrex), another COX-2 inhibitor, stayed on the market. The warning was drug-specific. Prescribers didn’t stop using all similar drugs-just that one. But here’s the trap: sometimes, a drug-specific warning turns out to be class-wide later. Rosiglitazone got a boxed warning for heart attacks in 2005. Pioglitazone didn’t. Then, more data came in. Pioglitazone carried similar risks. But because the original warning didn’t cover it, many doctors kept prescribing it thinking it was safer. That’s the danger of inconsistent labeling.

How Clinicians Can Tell the Difference

You don’t need to be a regulator to spot the difference. Here’s how to check:- Look at the warning language. If it says “all drugs in this class” or “this class of agents,” it’s class-wide. If it names one brand or chemical name, it’s drug-specific.

- Check DailyMed. The National Library of Medicine’s database color-codes warnings. Green means class-wide. Red means drug-specific. It’s free and updated daily.

- Review the FDA Drug Safety Communications archive. As of 2023, 18% of alerts were class-wide, 62% were drug-specific, and 20% were unclear. If the alert doesn’t specify, dig deeper.

- Ask: Is the mechanism shared? If all drugs in the class inhibit the same enzyme, cause the same metabolic byproduct, or bind to the same receptor, the risk is likely shared.

- Don’t assume based on names. Just because two drugs end in “-pril” or start with “cef-” doesn’t mean they share the same risks. Cephalosporins have 17 different agents-only some carry high allergy risks.

Common Mistakes and Pitfalls

Even experienced providers make these errors:- Mixing up recall classes with therapeutic classes. FDA recall classes (I, II, III) describe how dangerous a product is, not whether the risk is shared across drugs. A Class I recall means death or serious injury-but it doesn’t mean every drug in the group is affected.

- Assuming all drugs with similar names are the same. “Cef” doesn’t mean “same risk.” “-pril” doesn’t mean “same side effect.”

- Blindly avoiding an entire class after one warning. That’s what some doctors did after the fluoroquinolone alert. But for certain infections, these drugs are still the best option-when used carefully.

- Ignoring pharmacokinetic differences. Two drugs might be in the same class, but one is metabolized by the liver, another by the kidneys. That changes risk. A warning based on liver toxicity won’t apply to the kidney-metabolized version.

What’s Changing Now?

The system is getting smarter. In 2024, the FDA rolled out a new standardized taxonomy that now labels every warning as either “Class Risk” or “Agent-Specific Risk.” No more guessing. They’re also using AI to predict class effects before they’re obvious. IBM Watson Health’s tool analyzes over 15 million FAERS reports and identifies class signals with 89% accuracy. The FDA’s 2023 pilot program looks at molecular structures and shared metabolic pathways to spot hidden patterns. The 21st Century Cures Act (2016) now requires regulators to evaluate entire classes when a safety signal appears. The European Medicines Agency has had similar rules since 2012. But industry pushback is real. PhRMA says 37% of requested class-wide warnings since 2015 were challenged and dropped after manufacturers showed the risk was isolated to one drug. Still, the trend is clear: class-wide alerts are rising. They made up 12% of boxed warnings between 2000 and 2010. By 2011-2021, that jumped to 18%. Why? Better data. Better tools. And more pressure to protect patients.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a PhD in pharmacology to get this right. Start here:- Always check the exact wording of the warning.

- Use DailyMed or the FDA Drug Safety Communications archive to verify scope.

- When in doubt, ask: “Does this risk come from how the drug works-or from what it’s made of?”

- Remember: if a drug is pulled and others in the class stay, it’s likely drug-specific.

- Don’t assume. Confirm. Then act.

How do I know if a safety alert applies to all drugs in a class?

Look at the official wording from the FDA or the drug label. If it says “all drugs in this class,” “this class of agents,” or “all members,” it’s class-wide. If it names one specific drug (like “rosiglitazone”) without mentioning others, it’s drug-specific. Check DailyMed or the FDA’s Drug Safety Communications archive for color-coded or labeled alerts.

Can a drug-specific warning become class-wide later?

Yes. That’s happened several times. Rosiglitazone got a heart attack warning in 2005, but pioglitazone didn’t-until later studies showed both carried similar risks. This is why regulators now use more data before making decisions. But if you’re prescribing, always check for updated labels, especially if a drug you’ve been using has a warning and others in the class don’t.

Why do some drugs in the same class have different warnings?

Because drugs in the same class can have different chemical structures, metabolism pathways, or dosing. For example, cerivastatin was withdrawn for rhabdomyolysis, but atorvastatin and rosuvastatin weren’t-because they’re processed differently in the body. The FDA evaluates each drug’s unique profile, not just its group.

Do class-wide warnings mean I should stop prescribing all drugs in that class?

No. Class-wide warnings mean the risk exists across the group-but not that every patient is equally at risk. Sometimes, the benefit still outweighs the risk for certain patients. For example, fluoroquinolones are still used for complicated UTIs when other antibiotics fail. The warning tells you to be cautious, not to avoid the class entirely.

How often are class-wide warnings issued now compared to the past?

Class-wide warnings have increased. Between 2000 and 2010, they made up 12% of black box warnings. From 2011 to 2021, that number rose to 18%. Better data, AI tools, and regulatory requirements like the 21st Century Cures Act are pushing regulators to evaluate entire classes more systematically.

Are there tools I can use to help identify these alerts?

Yes. DailyMed (from the National Library of Medicine) color-codes warnings by scope. The FDA’s Drug Safety Communications archive is searchable and labeled. Tools like IBM Watson Health’s Drug Safety Intelligence analyze millions of reports to detect class signals. For most clinicians, DailyMed and the FDA site are free, reliable starting points.