Psychiatric Polypharmacy: Risks, Reasons, and Real-World Solutions

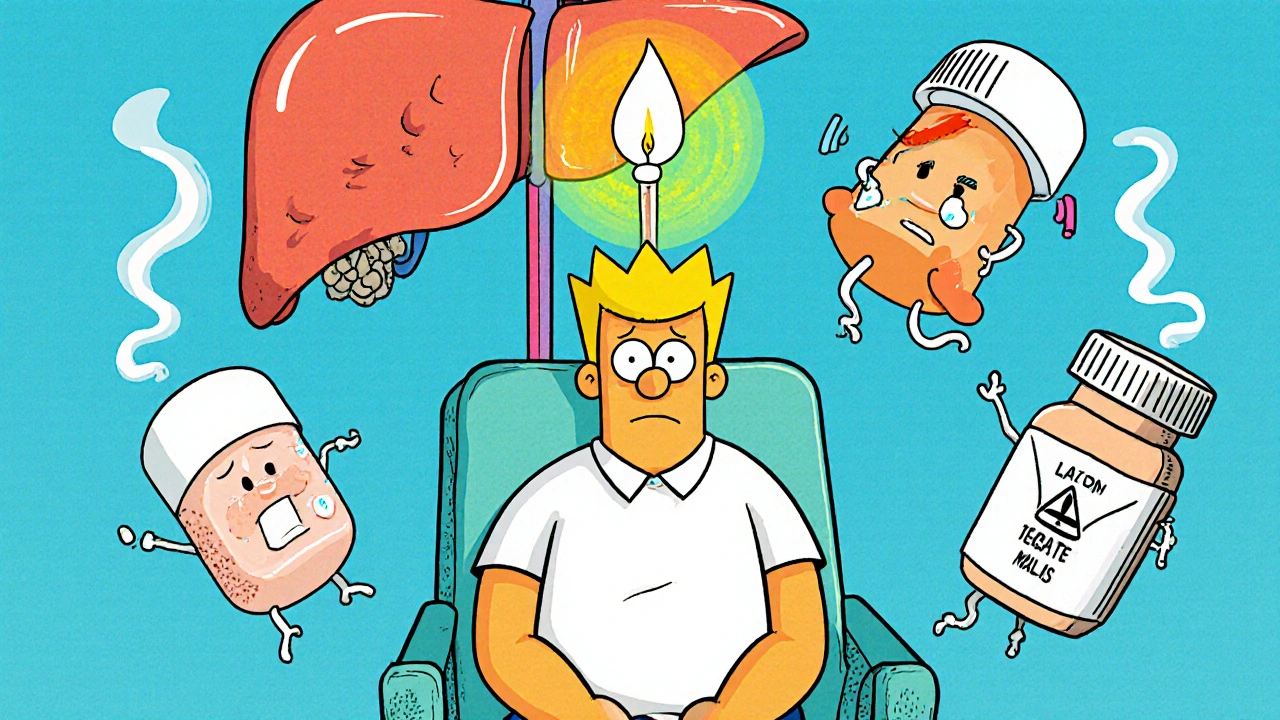

When someone takes psychiatric polypharmacy, the use of two or more psychiatric medications at the same time to treat mental health conditions. Also known as multiple psychiatric drug regimens, it’s often used when one drug doesn’t work well enough on its own. It’s not rare—about 1 in 4 people on antidepressants or antipsychotics are on three or more drugs. But it’s not always the best choice. Many times, it happens because symptoms didn’t improve fast enough, or doctors tried one drug after another without stepping back to see the big picture.

One of the biggest concerns with psychiatric polypharmacy, the use of two or more psychiatric medications at the same time to treat mental health conditions. Also known as multiple psychiatric drug regimens, it’s often used when one drug doesn’t work well enough on its own. is how these drugs interact. For example, combining certain antipsychotics, medications used to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other psychotic conditions. Also known as second-generation antipsychotics, they help reduce hallucinations and delusions. with antidepressants can increase the risk of weight gain, high blood sugar, or even heart rhythm problems. That’s why monitoring is key. People on these combos often need regular blood tests, weight checks, and heart monitoring. And yet, many patients don’t get those tests. Why? Because the focus stays on symptom control, not side effect management.

It’s also common for depression medication, drugs prescribed to treat major depressive disorder and other mood disorders. Also known as antidepressants, they include SSRIs, SNRIs, and others. to be added on top of an antipsychotic, even when the primary diagnosis is psychosis. Or someone with bipolar disorder might get a mood stabilizer, an antipsychotic, and an antidepressant—all at once. Each drug has its own side effect profile. Together, they can pile up: drowsiness, dry mouth, tremors, brain fog, or even metabolic syndrome. And the more drugs you take, the harder it is to know which one is causing what.

Some doctors use polypharmacy because they feel pressured to fix things fast. Others do it because insurance won’t cover therapy, or because patients don’t show up for follow-ups. But the truth is, simpler often works better. A single, well-chosen drug, paired with therapy and lifestyle changes, can outperform a cocktail of pills. Still, when polypharmacy is used, it should be intentional—not accidental. That means clear goals, regular reviews, and a plan to taper off if things aren’t improving.

You’ll find posts here that dig into exactly how this plays out in real life. From how antipsychotics, medications used to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other psychotic conditions. Also known as second-generation antipsychotics, they help reduce hallucinations and delusions. affect metabolism, to how to track side effects using dechallenge and rechallenge methods, to what happens when you mix meds for depression and anxiety. These aren’t theoretical discussions. They’re based on real patient experiences, clinical data, and practical advice you can use to ask better questions at your next appointment.