When you buy a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might not think about how its price was decided. But behind every low-cost medicine is a complex system used by governments to keep prices down. This system is called international reference pricing - and it’s how most European countries control what they pay for generic drugs.

What Is International Reference Pricing?

International reference pricing (IRP) is when a country looks at what other countries pay for the same medicine and uses that to set its own price. It’s not about copying the cheapest price - it’s about using a group of similar countries as a benchmark. For generic drugs, this means governments don’t just let manufacturers charge whatever they want. Instead, they compare prices across borders and set a reimbursement level that pharmacies and hospitals can use. This isn’t new. Italy started using it in 1984. By the 1990s, Spain, Portugal, and others followed. Today, 28 out of 32 European countries use IRP specifically for generic medicines, according to Medicines for Europe. The goal is simple: lower costs without cutting access. And it works. Countries using IRP for generics see prices 25% to 40% lower than those that don’t.How It Works for Generics - Not Just Patented Drugs

Many people assume IRP is used the same way for brand-name drugs and generics. It’s not. For patented drugs, countries often use external reference pricing - comparing prices from other nations directly. But for generics, most countries use internal reference pricing. Internal reference pricing means grouping together all generic versions of the same medicine - say, all 10mg tablets of metformin - and setting one reimbursement price. If a drug costs more than that group’s reference price, the patient pays the difference. If it’s cheaper, the pharmacy gets paid the full amount. This encourages competition among generic makers to be the lowest price in the group. Germany’s system, called AMNOG, is a good example. It sets the reimbursement price at the lowest-priced generic in the group plus 3%. That pushes manufacturers to undercut each other. The Netherlands goes further - they combine IRP with mandatory discounts and tendering, which has brought generic prices down 65% to 85% compared to the original brand.Which Countries Are Used as Benchmarks?

Countries don’t pick random nations to compare prices. They choose similar ones - economically, medically, and culturally. For Western Europe, the usual reference basket includes France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Eastern European countries often look to Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands. The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) recommends using 5 to 7 countries. Why? Because too many countries create confusion. A 2020 study by Professor Panos Kanavos from the London School of Economics found that countries using 5-7 reference countries got a 28% average price drop - and kept 97% of medicines available. But when countries used more than 10, the price drop only went up to 31%, while shortages jumped by 12%. Some countries tweak the math. Switzerland calculates its generic price as two-thirds of the average international price and one-third based on its own local prices. This keeps prices in line with Europe but protects against extreme swings.

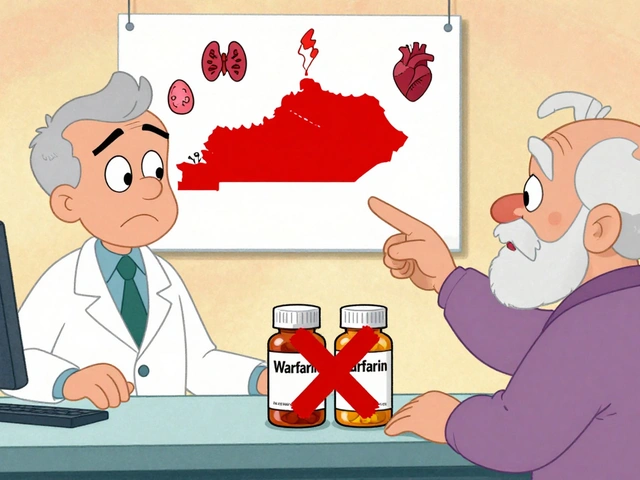

The Hidden Costs: Shortages and Market Exit

IRP isn’t perfect. Lower prices mean thinner margins. For generic manufacturers, profit margins are already small - often under 10%. When IRP pushes prices too low, some companies just walk away. Portugal saw 22 generic products disappear from the market in 2019 because manufacturers couldn’t make money at the set prices. Greece, during its financial crisis, slashed prices every quarter. The result? 37% of generic medicines had shortages between 2012 and 2015. Patients couldn’t get their usual brand, and pharmacists had to substitute - sometimes with products they didn’t trust. A 2023 RAND Corporation study warned that complex generics - like inhalers or injectables - are especially at risk. These drugs cost almost as much to make as brand-name drugs, but IRP doesn’t always account for that. In countries with strict IRP, new complex generic applications dropped 17% between 2016 and 2020, according to FDA data.How Patients and Pharmacists Experience IRP

Patients rarely see the policy. But they feel it. In Spain, generic substitution - where a pharmacist swaps a brand for a cheaper generic - rose from 52% in 2010 to 89% today because of IRP. That’s good for cost savings. But 63% of Spanish pharmacists reported occasional shortages of the lowest-priced generic, forcing them to offer alternatives. A 2021 OECD survey of 10 European countries showed that 78% of patients were happy with generic substitution. But 34% worried about quality differences. Some patients believe the cheapest pill isn’t the best. And while most generics are bioequivalent, the psychological effect matters. Pharmacists in Greece told patient advocacy groups that 41% of patients struggled to get their preferred generic brand during the peak of IRP cuts. They’d get a different one - sometimes with a different shape, color, or even inactive ingredients. That’s not a safety issue, but it’s confusing.Who Benefits? Who Loses?

The big winners are public health systems. Germany, France, and the Netherlands saved billions by using IRP. In 2022, Europe’s generic market was worth $140 billion - and IRP influenced 78% of it. Generic manufacturers have mixed feelings. Teva’s 2022 report said IRP led to a 9% revenue drop in Europe, even though they sold 15% more pills. Sandoz, on the other hand, said well-designed systems helped them grow market share in 18 countries. The real losers? Small manufacturers. Big companies like Teva and Sandoz can absorb price cuts. But smaller firms - the ones making niche generics - often can’t. They either exit the market or stop investing in new products.