Every time you pick up your prescription, you might be getting a different pill - same active ingredient, but a different color, shape, or name on the label. This isn’t a mistake. It’s generic drug switching, and it’s happening more than you think. In the U.S., over 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics. But here’s the catch: there are often four or five different generic versions of the same drug on the market, made by different companies. And your pharmacy might switch between them without telling you.

Why Do Generic Switches Happen?

It’s mostly about money. Insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers want the cheapest option. If Teva’s version of your blood pressure pill costs $5 and Mylan’s costs $3.50, they’ll switch you - even if you’ve been stable on Teva for years. Pharmacists are often instructed to substitute based on price alone, not your history or how you feel. This isn’t new. Since the 1980s, generics have saved U.S. patients over $300 billion. But the real issue isn’t generics themselves - it’s how often you’re moved between them. A 2023 study found that 12.8% of patients who started on a generic ended up switching back to the brand, mostly because of side effects or loss of effectiveness. For some drugs, that number is much higher.Not All Generics Are Created Equal

The FDA says generics must be “bioequivalent” to the brand-name drug. That means they deliver between 80% and 125% of the active ingredient compared to the original. Sounds close, right? But here’s the problem: two different generics could be at opposite ends of that range. One might deliver 82% of the drug, another 123%. That’s a 41% difference in how much medicine actually gets into your body. For most drugs - like statins or antibiotics - that variation doesn’t matter. Your body adjusts. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even small changes can cause real harm. These include:- Levothyroxine (for thyroid disease)

- Warfarin (a blood thinner)

- Tacrolimus (for transplant patients)

- Phenytoin and other antiepileptics

Real Stories: When Switching Goes Wrong

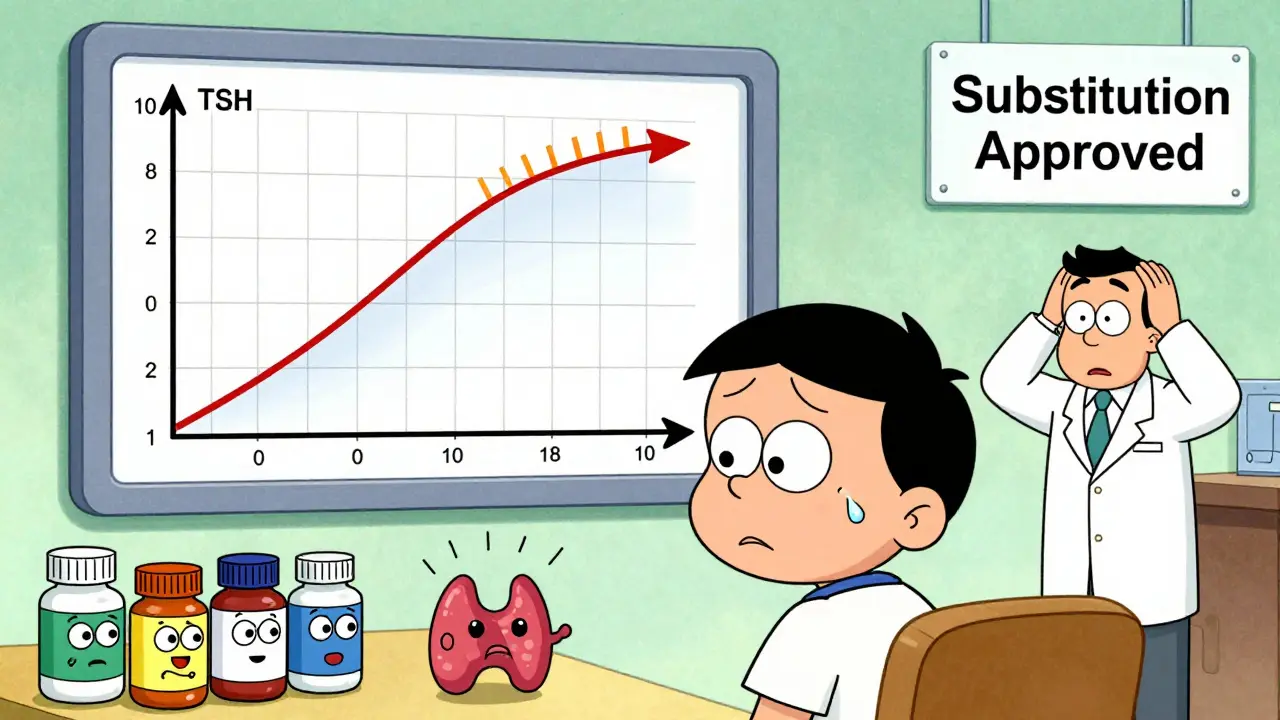

One Reddit user, u/PharmaPatient, wrote in March 2024: “My seizure medication switched from Mylan to Teva. Two weeks later, I had two breakthrough seizures. My neurologist checked my blood levels - they’d dropped 35%.” Another patient on Drugs.com said: “Every time my levothyroxine changes maker, I feel like I’m dying for a month. My doctor says it’s the same drug. But my body knows the difference.” These aren’t rare. A 2022 survey found that 32.7% of people on thyroid meds reported problems after a generic switch. For epilepsy drugs, the switch-back rate is as high as 44%. Meanwhile, people on statins or blood pressure pills rarely notice anything - their bodies handle the variation just fine.

Why Your Doctor Might Not Know

Here’s another hidden problem: most doctors don’t get notified when your pharmacy switches your generic. A 2023 AMA survey found that 62% of physicians only found out about the change when the patient called in panic - usually after side effects showed up. Pharmacies don’t have to tell you or your doctor. The system is built for efficiency, not communication. You get your pill. You take it. You assume it’s the same. But it’s not always.What You Can Do

You don’t have to accept random switches. Here’s how to take control:- Ask for the brand name - if you’re on an NTI drug, your doctor can write “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute” on the prescription. This legally blocks the pharmacy from switching.

- Know your pill - take a photo of your pill every time you get a refill. Note the shape, color, imprint code (like “A 123”). If it looks different, ask why.

- Check your lab results - if you’re on warfarin, levothyroxine, or tacrolimus, ask your doctor to check your levels after any switch. Don’t wait until you feel bad.

- Ask your pharmacy to lock in your manufacturer - many pharmacies will honor a request to keep you on one generic version, especially if you’ve had issues before.

- Use a single pharmacy - chain pharmacies often switch generics more frequently than independent ones. Stick with one place so they can track what you’ve been on.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The FDA is starting to wake up. In 2023, they launched a pilot program requiring generic manufacturers to report any formulation changes that could affect how the drug works. In 2024, Medsafe (New Zealand’s drug regulator) issued new guidance saying levothyroxine should not be switched between brands unless absolutely necessary. The Association for Accessible Medicines is also working on standardized pill identification - so even if the name changes, you’ll know it’s the same version. But until then, the burden falls on you.When Switching Is Fine - And When It’s Not

Let’s be clear: generics are safe and effective for most people. If you’re on metformin, amoxicillin, or lisinopril, switching between generics is unlikely to cause problems. Many patients have taken multiple versions for years with no issues. But for NTI drugs, the data is clear: frequent switching increases risk. A 2021 statement from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy warned that “frequent switching between multiple generic manufacturers may compromise therapeutic outcomes” for these drugs. The goal isn’t to stop generics. It’s to stop random, unmonitored switches for drugs where precision matters.Bottom Line

Generic drugs save billions. But they’re not all interchangeable - especially for life-critical medications. If you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic index, don’t assume your pill is the same just because the name is. Know what you’re taking. Track changes. Ask questions. Your health isn’t a cost-saving experiment.Can I be switched between different generic versions of my medication without my doctor’s approval?

Yes. In most cases, pharmacists can substitute one generic for another without telling you or your doctor - unless the prescription says “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute.” This is legal under U.S. pharmacy laws, but it’s not always safe, especially for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index like levothyroxine or warfarin.

Which generic medications are most likely to cause problems when switched?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) are the biggest concern. These include levothyroxine (for thyroid), warfarin (blood thinner), tacrolimus (transplant rejection), phenytoin and other antiepileptics, and lithium. Small changes in blood levels can lead to serious side effects - seizures, bleeding, organ rejection, or thyroid dysfunction.

How do I know if my generic medication has changed?

Check the physical appearance of your pill - color, shape, size, and imprint code (the letters or numbers stamped on it). If it looks different from your last refill, ask your pharmacist which manufacturer made it. You can also look up the imprint code on websites like Drugs.com or Medscape. Taking a photo each time you refill helps you spot changes.

Should I ask my doctor to write “Do Not Substitute” on my prescription?

If you’re on an NTI drug and have had problems with switching before, yes. It’s your legal right. Many patients on levothyroxine or warfarin request this. Your doctor may need to explain to your insurance, but most will support it if you’ve had clinical instability. Some insurers will still approve it if you’ve had a bad reaction.

Are brand-name drugs better than generics?

For most medications, no. Generics contain the same active ingredient and meet the same FDA standards. But for NTI drugs, brand-name versions often have more consistent formulations. If you’ve been stable on a brand, switching to a generic - or switching between generics - can cause problems. The choice isn’t about quality; it’s about consistency.

What should I do if I think a generic switch caused side effects?

Don’t ignore it. Contact your doctor immediately. If you’re on a blood thinner, thyroid med, or seizure drug, ask for a blood test to check your levels. Keep a symptom log - note when you switched, what you felt, and when it improved. This helps your doctor determine if the switch caused the issue. Report it to the FDA’s MedWatch program if you believe it’s a safety concern.