Medication Interaction & Side Effect Explorer

Understand how your medications might interact with each other and your body based on scientific principles from the article.

This tool explains common medication interactions based on the science behind side effects. It simulates how drugs interact through pharmacokinetics (how your body processes drugs) and pharmacodynamics (how drugs affect your body).

Science note: Many side effects occur when drugs interact with enzymes like CYP3A4 (in your liver) or target multiple receptors in your body. This tool focuses on the most common interactions mentioned in the article.

Why This Matters

The article explains that 6-7% of hospital admissions in older adults are due to drug interactions. By understanding potential interactions, you can work with your doctor to minimize risks.

Remember: Never stop taking prescribed medication without consulting your doctor. If you experience unusual symptoms, contact your healthcare provider immediately.

Every year, millions of people take medications to feel better - but many end up feeling worse. A headache pill gives you nausea. An antibiotic causes a rash. A blood pressure drug makes you dizzy. It’s not just bad luck. These aren’t random glitches. They’re predictable outcomes of how drugs interact with your body at a molecular level. Side effects aren’t flaws in the system - they’re the inevitable result of biology being incredibly complex, and drugs being blunt tools trying to fix intricate problems.

What Exactly Are Side Effects?

Side effects, medically called adverse drug reactions (ADRs), are any unwanted or harmful responses to a medication. The FDA defines them as effects that are “possibly related” to the drug. That’s important: not every bad feeling after taking a pill is a side effect. But when it happens often enough, and science can link it to the drug, it’s classified as one. About 75-80% of side effects are predictable. That means doctors and scientists understand why they happen. The other 20-25% are unpredictable - they strike without warning, even in people who’ve taken the drug before without issue. These unpredictable reactions are rare, but they’re the ones that make headlines: severe rashes, liver failure, or life-threatening allergies. In the U.S., ADRs are responsible for about 7% of all hospital admissions. That’s over a million people a year. And it costs the healthcare system roughly $30 billion annually. These aren’t minor inconveniences. They’re serious, costly, and often preventable.How Drugs Interact With Your Body - And Why That Causes Trouble

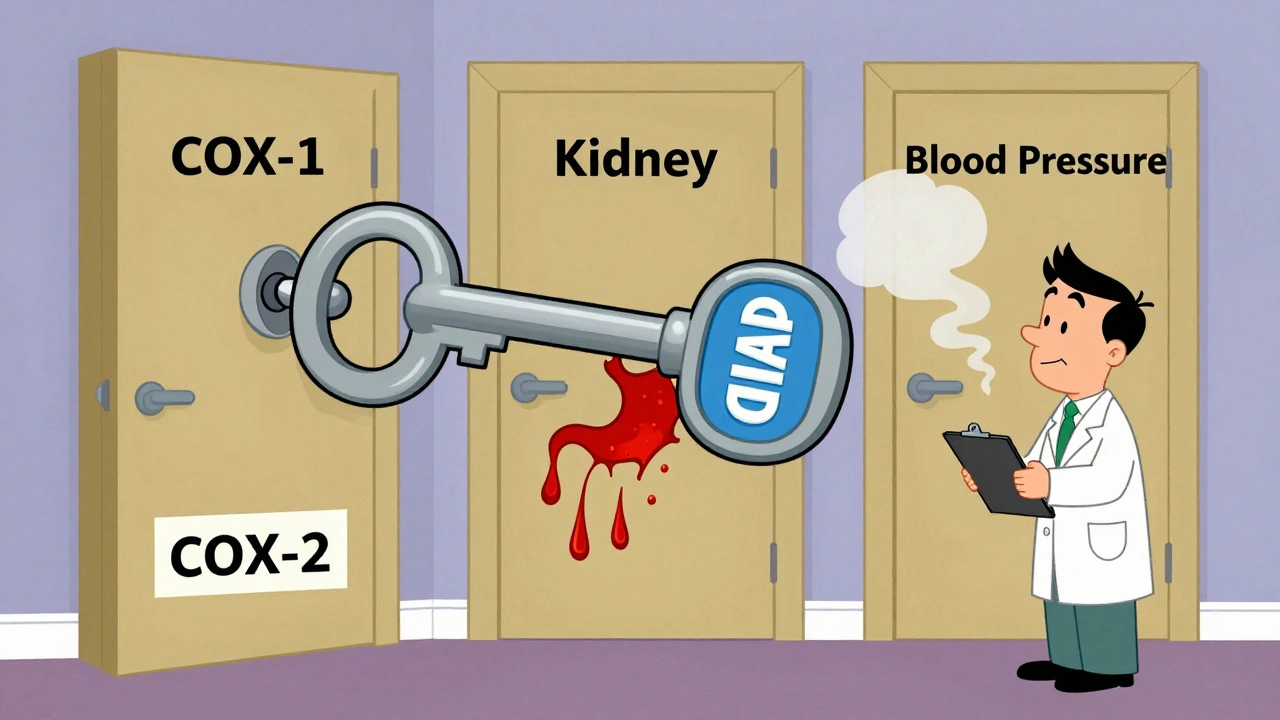

Drugs don’t magically target only the problem area. They travel through your bloodstream, pass through tissues, and bind to molecules wherever they fit. Think of it like trying to fix a broken lock with a key that also opens other doors. There are two main ways this goes wrong: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacokinetics is about what your body does to the drug. This includes how it’s absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and cleared. Genetic differences play a huge role here. For example, some people have a version of the CYP2D6 gene that makes them slow metabolizers of codeine. That means their bodies turn codeine into morphine too slowly - or too quickly. If they’re a fast metabolizer, they can build up dangerous levels of morphine, leading to breathing problems. About 5-10% of Caucasians are slow metabolizers. For them, standard doses can be risky. Pharmacodynamics is about what the drug does to your body. Most drugs work by binding to specific receptors - like a key fitting into a lock. But sometimes, the key doesn’t just open one lock. It opens others nearby. Take NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen. They’re designed to block COX-2, an enzyme that causes pain and inflammation. But they also block COX-1, which protects your stomach lining. That’s why 15-30% of regular users develop stomach ulcers. The drug isn’t “bad.” It’s just doing two things at once - one helpful, one harmful. Another example is haloperidol, used for psychosis. It blocks dopamine receptors in the brain to reduce hallucinations. But dopamine receptors are also in the basal ganglia, which control movement. So, 30-50% of patients on haloperidol develop tremors, stiffness, or involuntary movements - side effects that look like Parkinson’s disease.When Drugs Mess With Your Cell Membranes

Most people think of drugs as targeting specific proteins. But a 2021 study from Weill Cornell Medicine showed something surprising: many drugs don’t just bind to proteins - they change the environment around them. Drugs that interact with cell membranes - like antibiotics, antifungals, or even some heart medications - can alter the membrane’s thickness, flexibility, or charge. These changes mess with proteins that sit inside or across the membrane. It’s like shaking a table and watching everything on it wobble, even if you didn’t touch it directly. This explains why some drugs cause a wide range of side effects across different organs. They’re not hitting one target - they’re disturbing the entire cellular neighborhood.

Immune System Reactions - The Body’s Overreaction

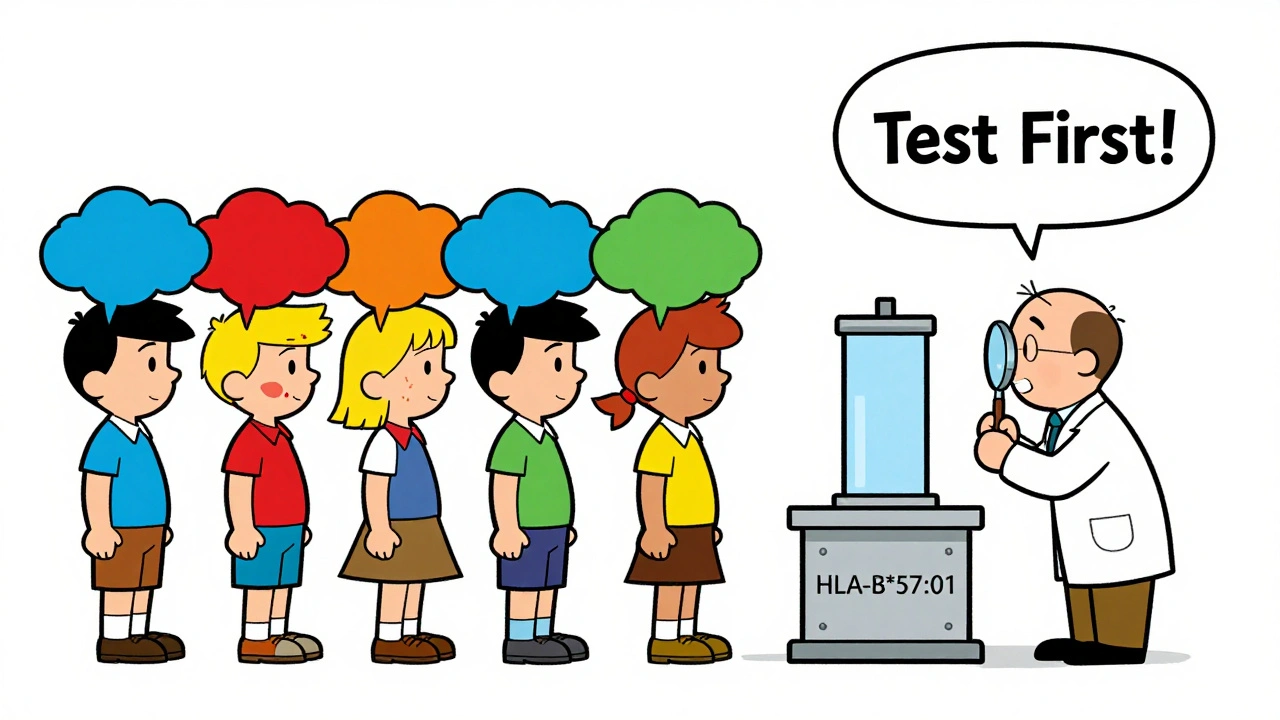

About 5-10% of side effects are immune-mediated. These are the allergic reactions you hear about: rashes, swelling, anaphylaxis. But not all immune reactions are the same. Type I reactions (IgE-mediated) happen fast - within minutes to hours. Penicillin is the classic example. About 1-5 in every 10,000 people who take it will have a life-threatening reaction. That’s rare, but it’s why doctors ask about penicillin allergies before prescribing any antibiotic. Type IV reactions are slower. They’re T-cell driven and can take days or weeks to show up. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), a terrifying skin reaction, falls into this category. It’s rare - only 1-6 cases per million people per year - but it’s often triggered by drugs like allopurinol, sulfonamides, or seizure medications. Here’s where genetics becomes critical. People with the HLA-B*57:01 gene variant have a 50-100 times higher risk of a dangerous reaction to abacavir, an HIV drug. Before routine genetic testing, about 5-8% of patients had this reaction. Now, doctors test for the gene first. If it’s present, they don’t give the drug. The reaction rate dropped to under 0.5%.Drug Interactions - When One Pill Makes Another Dangerous

Taking multiple medications is common, especially for older adults. But mixing drugs can turn safe treatments into hazards. Grapefruit juice is a notorious culprit. It blocks an enzyme called CYP3A4, which breaks down many drugs. If you take felodipine (a blood pressure drug) with grapefruit juice, your blood levels can spike by 260%. That can cause dangerous drops in blood pressure. Rifampicin, an antibiotic used for tuberculosis, does the opposite. It speeds up the breakdown of other drugs. It can reduce digoxin levels by 30-50%, making it useless for heart failure. NSAIDs can also interfere with kidney function. When taken with methotrexate (used for arthritis or cancer), they reduce how fast the body clears the drug. That can lead to bone marrow suppression - a life-threatening drop in blood cells. In older adults, drug interactions cause 6-7% of hospital admissions. The risk jumps dramatically when someone takes five or more medications at once.

How Doctors Fight Side Effects - Before They Start

The good news? We’re getting better at preventing side effects before they happen. Genetic testing is now standard for certain drugs. Before giving abacavir, doctors test for HLA-B*57:01. Before prescribing clopidogrel (a blood thinner), they test CYP2C19 status. Poor metabolizers get alternative drugs - no more risk of heart attack from ineffective treatment. Therapeutic drug monitoring is used for drugs with narrow safety margins. Digoxin, for example, must stay between 0.5-0.9 ng/mL. Too low? It doesn’t work. Too high? It can kill you. Regular blood tests keep it in range. Prophylactic drugs are often added to prevent side effects. If you’re on long-term NSAIDs and have a history of ulcers, your doctor will likely prescribe a proton pump inhibitor (like omeprazole). Studies show this cuts ulcer risk by 70-80%. Dose titration helps too. Starting SSRIs at low doses reduces nausea and dizziness in the first week - side effects that affect 20-30% of users. Slowly increasing the dose lets your body adjust.The Future: Smarter Drugs, Fewer Side Effects

The next big leap is in drug design. Scientists are using AI to predict off-target effects before a drug even reaches humans. A 2023 study in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery showed AI models could cut late-stage trial failures due to toxicity by 25-30%. That’s billions saved and safer drugs faster. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative now tracks side effects in real time across 300 million patient records. It caught that pioglitazone (a diabetes drug) increased heart failure risk by 1.5-2 times - something clinical trials missed. Researchers are also mapping which membrane proteins are most vulnerable to bilayer disruption. The goal? Design drugs that don’t disturb cell membranes at all.Bottom Line: Side Effects Aren’t Random - They’re Understandable

Side effects aren’t a sign that medicine is broken. They’re a sign that biology is complex - and we’re still learning how to navigate it. Every drug has trade-offs. The goal isn’t to eliminate side effects entirely - that’s impossible. It’s to minimize them through science: genetics, monitoring, smart prescribing, and better drug design. If you’ve had a bad reaction to a medication, don’t assume it’s your fault. Talk to your doctor. Ask if genetic testing is available. Ask if there’s a safer alternative. Your body isn’t failing you - it’s just responding to chemistry you didn’t know existed.Are side effects always dangerous?

No. Many side effects are mild and temporary - like nausea from an antibiotic or drowsiness from an antihistamine. These often fade as your body adjusts. But some side effects can be serious or life-threatening, like liver damage, severe allergic reactions, or dangerous drops in blood pressure. The key is knowing which ones require immediate medical attention versus those you can manage with your doctor’s guidance.

Can you outgrow a drug side effect?

It depends. If the side effect is due to your body’s metabolism - like slow processing of a drug - your genes don’t change. So you won’t outgrow it. But if it’s a temporary reaction like nausea or dizziness, your body may adapt over time. That’s why doctors often recommend starting with a low dose. However, if you’ve had a true allergic reaction - like swelling, hives, or trouble breathing - you should never take that drug again.

Why do some people get side effects and others don’t?

Genetics, age, liver and kidney function, and other medications all play a role. Two people can take the same drug at the same dose and have completely different experiences. One might feel fine. The other might get a rash or dizziness. That’s because their bodies handle the drug differently. For example, people with certain gene variants process drugs slower or faster. Others have immune systems that overreact. It’s not luck - it’s biology.

Are natural supplements safer than prescription drugs?

No. Just because something is “natural” doesn’t mean it’s safe. Many herbal supplements interact with prescription drugs. St. John’s Wort can reduce the effectiveness of birth control, blood thinners, and antidepressants. Goldenseal can interfere with liver enzymes, just like grapefruit juice. Supplements aren’t tested the same way as FDA-approved drugs, so their side effects and interactions are often unknown.

Can side effects show up years after starting a drug?

Yes. Some side effects are delayed. Weight gain from antipsychotics like olanzapine can happen over weeks or months. Bone loss from long-term steroid use takes years. Certain drugs can trigger autoimmune reactions or increase cancer risk over time. That’s why regular checkups and monitoring are important - even if you feel fine.

What should I do if I think a medication is causing side effects?

Don’t stop taking it without talking to your doctor. Some side effects are harmless. Others need immediate attention. Keep a log: when the symptom started, how often it happens, and what you were taking. Bring this to your doctor. Ask: Could this be related to the drug? Is there an alternative? Should I get tested? Your input helps your doctor make smarter decisions.